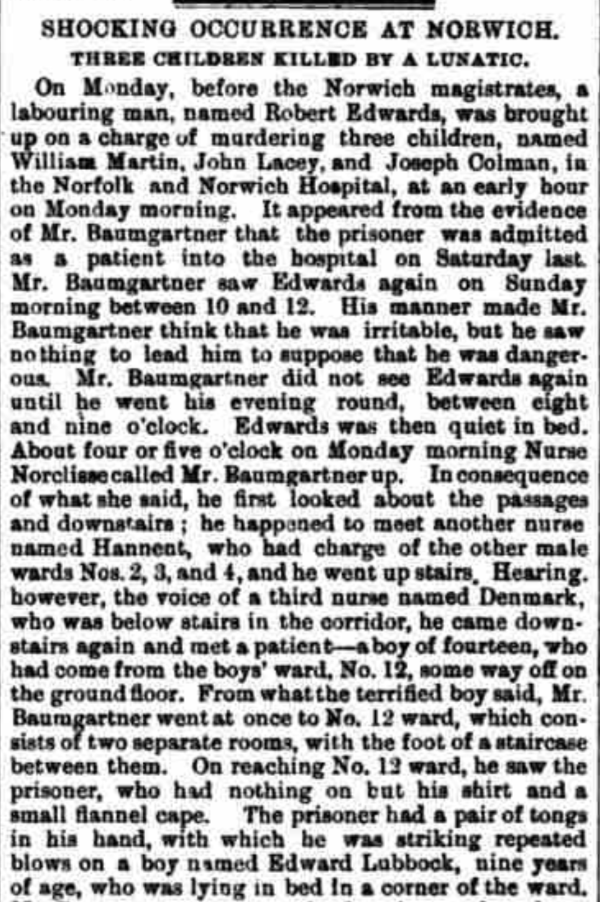

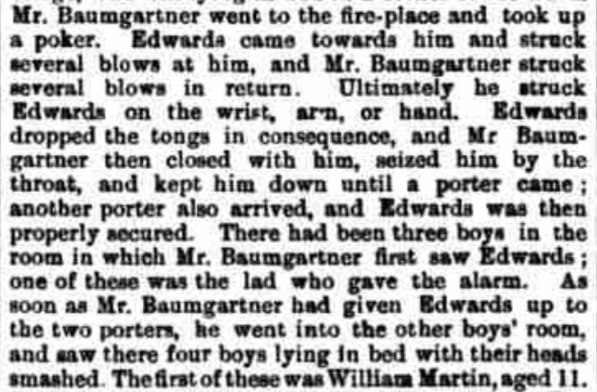

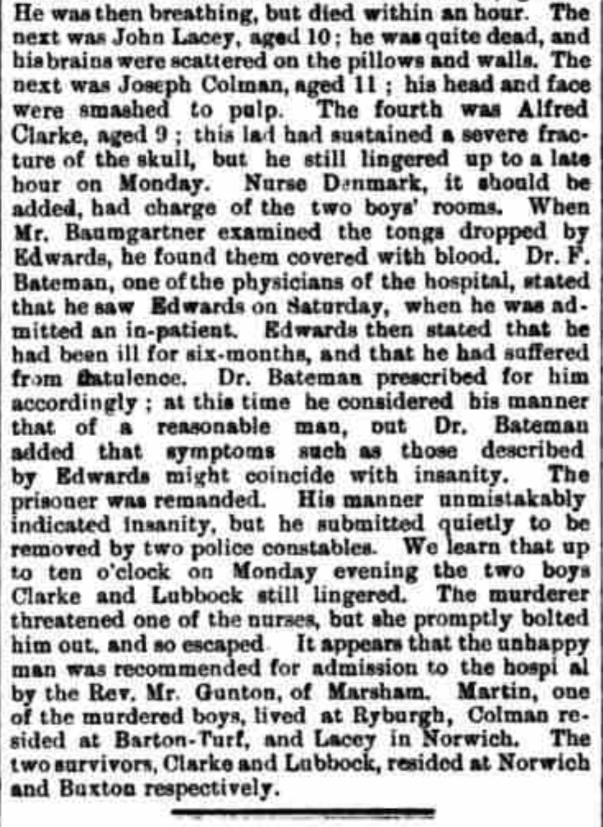

I came across this tragedy quite by accident some years ago when searching the British Newspaper Archive for Great Ryburgh when it first was made available online through the Public Library. It came as a shock to chance on this distressing and very gruesome reportage which I reprint here as I first encountered it in the Oxfordshire Weekly News for December 15th 1875:

I kept the cutting on file but didn’t really think about it further for some years until we started work on the building known then as the Gas House Project. The new pathway through from the car park to the churchyard was going to pass through an overgrown area where the church’s compost heap/bonfire had become established. Clearance of this area could only be an added bonus of the project. As we dug through the accumulated mound we encountered long felled tree stumps, randomly scattered grave kerb stones, a headstone plinth and two entire headstones, one of which was that of William Martin. Shock again, this time from the neglect that this little boy’s resting place had suffered. This is what prompted the naming of the building so he would not fall into oblivion again.

Shortly after this a couple came to the churchyard to find William’s grave. They turned out to be Barrie and Barbara Martin, William’s great nephew and his wife and for the reasons above had been unable to find the grave when they had been to look some years previously. They were delighted to find it and slightly taken aback that his history was known to me as they had not long since learned of this family tragedy uncovered by Barrie's sister Davina Martin’s research.

During the course of the building I also began to do some further research having read the history, painstakingly transcribed and compiled by Davina Martin. This is to be found as a separate page by clicking HERE

Photos of progress in the building especially in regard to its dedication can be found HERE

For me, the next port of call was to try and find out more about the boys themselves. Extensive searching of the BNA revealed how “viral” the contemporary press coverage quickly became, some of it reprinted verbatim from the earliest Norwich papers’ reports, others condensed and précised nationwide. The hundreds of column inches devoted to the story centred on the gory details of the inquest revealing the fact that the inquest jury actually had to attend the scene of crime in person before the poor victims’ bodies could be removed for burial. There was much reporting of the witness statements but my overwhelming impression of the coverage is of the concern as to who was to blame for the murderer, Robert Edwards being admitted to the N&N in the first place and with that, the reputation of the professionals involved. Whereas, nearly all that is to be found in the press concerning the victims and their families is present in the clipping at the head of the page. It was this, to me, glaring omission that spurred further research with the help of my Ryburgh friends, Drs. Gill and Tony Waldron. Their professional interest was understandably partly centred on the murderer and an explanation of the causes of his violent action. It is through their investigations in Norwich and Reading that they were able to send me details of Robert Edwards' concluding part in this tragic tale following his apprehension:

Robert Edwards was detained in Norwich jail and after three appearances in a week before magistrates was committed for trial on a charge of wilful murder. According to the medical notes made in the prison, his mental state varied between quiet bewilderment and utter derangement. He could give an account of the attack which he apparently did with a certain degree of savagery and his behaviour is described as varying from rationality to childish drama. He continued to complain of stomach pain and was often confined to bed. A couple of weeks after his imprisonment he assaulted "one of the prisoners in attendance on him” by striking him over the head with a wooden clog, seemingly entirely unprovoked. This attack precipitated a request to the Home Secretary for his committal to Broadmoor Hospital which was granted on 11 January 1876.

Broadmoor Hospital in Berkshire was built after the recognition that there was inadequate provision for the criminally insane and opened in 1863 with beds for 400 men and 100 women. It was designed and run as an asylum and not a prison, with the exception of a very secure perimeter wall.

The journey from Norwich to Broadmoor must have been an ordeal for all concerned. Edwards was escorted, almost certainly in chains, by two prison officers. Their journey started at Norwich station, and from there to Liverpool Street in London. They crossed by cab to Waterloo Station where they boarded a train to Wokingham. At Wokingham they were met by the Broadmoor Omnibus which took them the final five miles to the asylum.

In Broadmoor Edwards was measured and weighed. He was 5 ft 5½ ins and weighed 7 st 10 lbs. He was described as weak, feeble, and emaciated. His mental state was clearly abnormal. He was often restless and noisy, beating on his door and shouting, or quiet and subdued. He remained in Broadmoor until his death from pneumonia in July 1879. For most of his stay he was nursed in the infirmary ward and was usually in bed suffering from abdominal pain and remaining underweight despite a good appetite. Sometimes his physical condition seemed to improve but never completely. His mental state was always abnormal and he was described as having delusions that he was being poisoned and that his sister had been murdered. There were no further violent episodes, however. In April 1876 he was declared as unfit to plead and was never tried for the killing of the boys.

It is not possible retrospectively to diagnose his physical condition which was obviously severe. The evidence for his mental condition points to a severe depression with delusions and probable hallucinations as well. Sudden violent attacks are not a feature of this illness and where they do occur, they are as the result of the abnormal belief suffered by the patient. An example of this would be that the devil had entered the victim and a great disaster would befall others as a result. In such an example, the victim would be killed to protect others. Speculation about Edwards’ motive for the murders does not help to understand what truly was their cause. It is true that dangerousness of this type is extremely rare and virtually impossible to predict.

********************

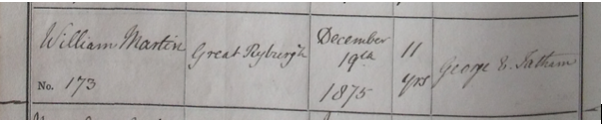

My first task was to look at the local context which entailed checking the history of the Martin family in the village and anything that might remain in the church by way of a record. A copy of William’s death certificate is the only non press related statement of his fate i.e. that he was murdered. The Burial register entry told the basic facts of the burial which generally is all such registers do:

The Revd. George Edmund Tatham and his entry recording the death of William Martin in the Burial Register.

From here we come back to the grave’s headstone which was excavated from the former bonfire site:

This very basic inscription has at its base the text “O Boys be strong in Jesus” which gave rise to the thought that the other boys may have been similarly remembered. This set off a train of investigation to find the graves of the other boys to see if they were similarly styled and worded.

Further investigation of the random fragments of kerb edgings that were found in the bonfire area and were of a similar stone suggest that the original lettering on the grave may have read as follows:

looking unto / Jesus / who endured / the cross /

O boys be strong in Jesus

It is well

Locating the 3 other grave sites has not been an easy task but the chance to visit that of Joseph Thomas Colman at Barton Turf shows a deteriorating headstone, in this case due to the soft type of stone used and shows from the inscription that they were probably all individual memorials. Joseph's headstone lies in a very prominent position by the churchyard wall, in front of the west wall of the splendid tower of St Michael's Church

This reads as follows:

In

loving memory of

Joseph Thomas

the only son of

Robert & Ann COLMAN

who was suddenly called

from time into eternity at the

Norwich Hospital December 13th 1875

aged 11 years

Short was my race, long is my rest

God call'd me when he thought it best

My time was come I in a moment fell

and had not time to bid my friend farewell.

Of the two remaining graves, that of John Lacey has so far proved impossible to find.

Alfred Clarke was baptised as Ebbage, (Clarke being the surname of his stepfather) and so buried under that name in the Earlham Cemetery. The location is known but I was unable to find any headstone in the area specified by the records. If the grave consists only of kerbs none of those that I could locate identified Alfred Clarke.

What has been an unanswered question is how did their families afford the cost of such memorials. Drs. Gill and Tony had looked in the N&N Hospital Management Report for 1875 and found the following:

“Extraordinary Expense £13-11/- for funeral expenses and coffins for 3 patients”

No names are mentioned but assuming these are referring to William, John and Joseph this amount should have been sufficient for the basics but certainly not the headstones. Correspondence with local antiquary and authority on funeral customs, Julian Litten confirms the following:

“So pleased to hear that the new building is to be named after William Martin.

£13 11s would have been sufficient to cover the cost of the funerals of all three boys. Then, as now, local authorities and hospitals financed funerals under tender from local undertakers. I very much doubt that a simple elm coffin with basic handles would have come to much more than £3 each, the remaining £4 11s being the cost of transporting each body to their respective places of burial.

Joseph Colman's headstone would have cost something in the region of £10. There was no compunction on the hospital/local authority to provide anything more than the funeral expenses and so one would assume that the cost of the headstone was probably met by both then parents and (not to put it too crudely) a "whip round" amongst the other villagers.”

Consultation of the 1876 N&N Hospital Management Report found no such similar extraordinary provision for Alfred Ebbage Clarke who didn’t succumb to his injuries for a further 2 months after the attack.

*****************

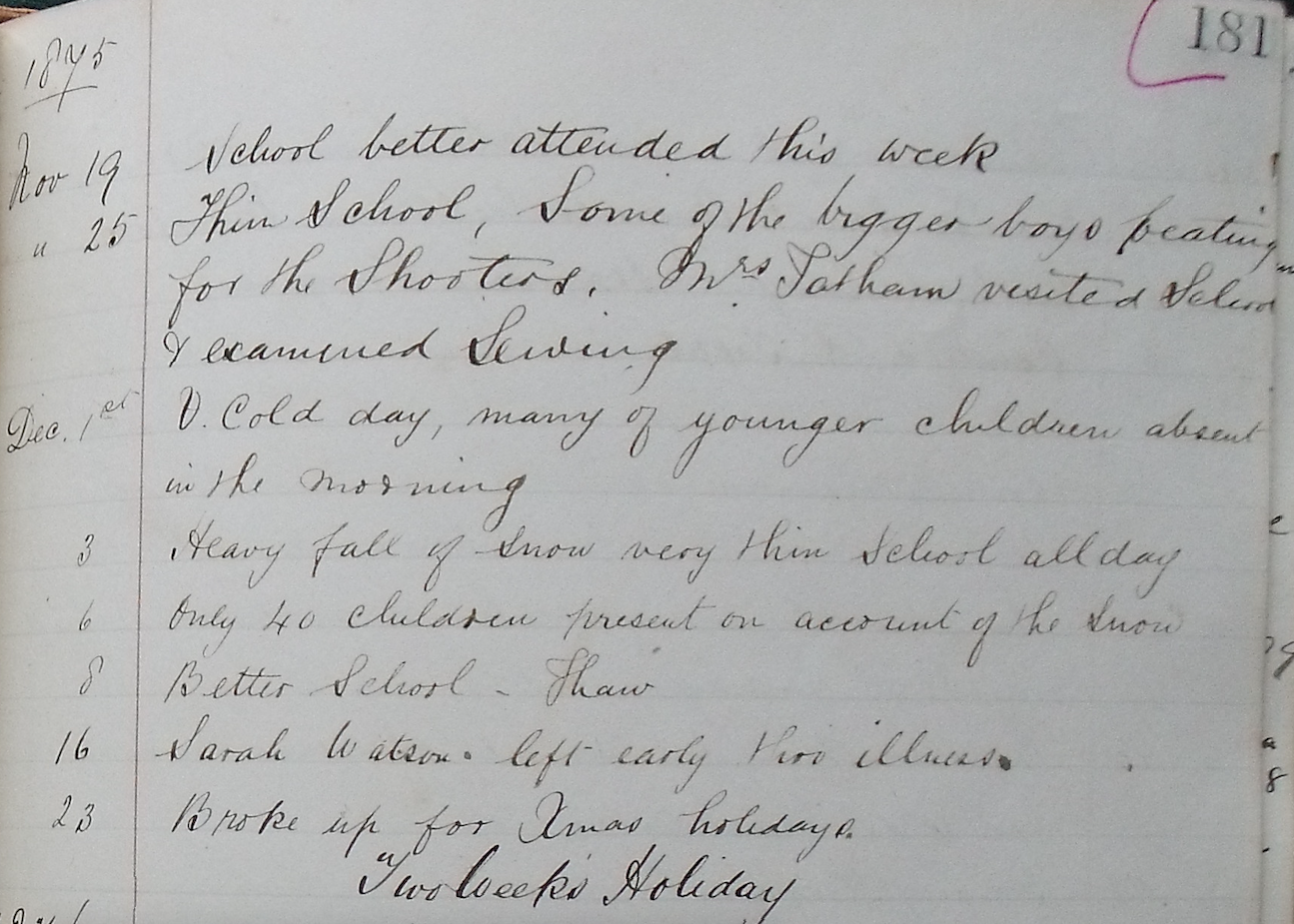

Examination of the Ryburgh school log book, which at this time was sparsely annotated showed no mention of the occurrence which happened just before the Christmas holidays. It is to be hoped that this bleak page didn’t reflect the attitude of the whole village:

There is no little irony in this apparent disinterest in view of the fact that William’s grandfather Gent Martin was Master of Ryburgh’s National School (and Sunday School) from 1829. Prior to that he was described in the church registers as a “shopkeeper”. It is not unreasonable to think that he was able to make this transition with the help of the most likely educated presence in the village, then Rector, Revd. William Ray Clayton. To judge from the register entries, he was quite hands-on for the first 12 years of his incumbency during the period that the current rectory was built.

Davina Martin has been able to trace William’s great, great grand-parents who were John Martin b1720 and Hannah Young b1719. Their birthplaces are unknown at present. They married in 1745 in Grimston and were both in their 30s. They had ten children 3 of whom did not survive infancy. John died in 1793 and Hannah in 1794' Both are buried at Weasenham.

Their youngest child Matthew, William’s great grandfather was born in 1761 at Weasenham All Saints where the family had spent most of their lives.

He married Mary Gent (probably pronounced with a hard G like the town in Belgium) at Kings Lynn St Nicholas on January 22nd 1789. He kept a Grocer and tallow chandler’s shop in Kings Lynn High Street but had arrived in Gt. Ryburgh (or possibly Little Ryburgh) by June 26th 1794 when their son Gent was baptised at St Andrew’s. The register gives his date of birth as May 31st 1794.

Mary died in January 1841 and Matthew lived just over a year longer, in time to be found in the first Little Ryburgh Census of 1841. He was buried on March 21st 1842 aged 85 joining Mary in the churchyard at Little Ryburgh. In the Census he is described as a “pauper” and is living with “Schoolmaster” Gent and his wife Frances Elizabeth Beaurain and their four children, Charles Gent, William, Mary Ann and John.

Gent and Frances were married on April 1st 1823 at St Margarets King’s Lynn and as mentioned above, probably grew up in his father Mathew’s shop in Ryburgh, though it is not known where and is very difficult to even guess in this pre-Census era.

By the 1851 Census, Gent is now described as “Schoolmaster (pauper)”. And when he died, was buried at St. Andrew’s on December 30th 1859.

In the 1861 Census. his widow, Frances Elizabeth is now described as “late Governess”. She had originally come to Norfolk, from her birthplace in the parish of St Botolph Bishopsgate, as a governess. It is she who heads the household with her two younger sons William a shoemaker and John an Ag. Lab., both as yet unmarried.

Davina has found that Frances died in 1872 at Thorpe St Andrews, Norwich in the asylum from senile decay and dementia and where she was described as the widow of a tailor.

Eldest son, Charles Gent had married Sarah Empson from Stibbard in 1854 and only daughter, Mary Ann had married James Empson from Stibbard earlier that same year when both parents were alive.

William aged 33, was married on Christmas Day 1863 to the 27 year old Mary Ann Bangay.

In May 1858 John had been a witness to the marriage in St Andrew’s of George Smithson and Elizabeth Toll both from Great Ryburgh. By January 1862 Elizabeth was a widow with two children, George Toll born 1856 and Elizabeth Smithson born 1860.

Elizabeth Smithson and John Martin were also married in the 4th quarter of 1863 and their eldest child, our William Martin of the Building was born on 23rd. April 1864 as his headstone pictured above states. Henry George followed in 1867, baptised December 11th and Fred in 1869 baptised on 13th January. Their step-sister, 9 year old Elizabeth Smithson died in January 1868 and was buried at St. Andrew’s on January 27th 1868.